Is Blur the Radiohead of Britpop? (pt. 3)

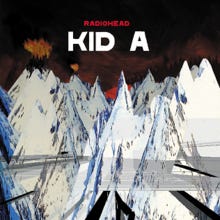

In which we compare and contrast 13 and Kid A/Amnesiac

Welcome back to me rambling about this incredibly niche topic and question that nobody is asking but me. In the last post, we briefly looked at Blur’s album The Great Escape, but mostly focused on comparing and contrasting OK Computer and Blur to see the similarities and differences between the albums, the bands, and the creative direction each was influenced by and moving towards. In this post, we will be doing the same for the next album(s) from each band, Kid A and Amnesiac for Radiohead and 13 for Blur. Both were even more of stylistic shifts than their previous works; I would say even utter stylistic abandonment. And, both remain incredibly influential and profound works of art to this day.

To begin with, I want to explain why I am going to be considering Kid A and Amnesiac as essentially one album. It is true that they are very different works of art. Both the band and any devoted Radiohead fan will know that they are considered separate entities, usually. They were, however, recorded in the same sessions and released within a year of each other. As such, they do have a lot in common. Yes, it is true that Amnesiac is not just the B-sides of Kid A; it is a fully fleshed out album of it’s own. But for the sake of brevity and due to the similarities it does share with its predecessor, I will be considering them as more or less the same album for this discussion. Also, just recently in 2021, both albums were remastered and released together as Kid A Mnesia, so clearly the band must at least find them similar enough to be packaged and sold together as part of one package. So for the sake of our discussion, I will be doing the same.

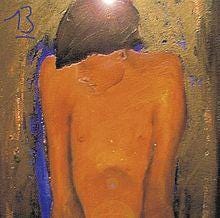

So let us begin with 13, which came out a year before Kid A, in 1999. After the commercial and critical success of Blur, which as we have established already was a complete departure from everything their sound had been, the band wanted to keep innovating. This stands in stark contrast to the lead up to Kid A, which was the result of burnout and tension and stress. 13 also had quite a bit of those things involved in its production as well. Damon Albarn had a heroin problem, and Graham Coxon was struggling with alcoholism. But perhaps the single biggest factor in influencing the sound of the album that the band would come to make was the end of Albarn’s very publicised romantic relationship with fellow britpop veteran Justine Frischmann. Their relationship had been strained for a while already, due to Albarn wanting to have children as well as Frischmann’s continued friendship with her ex boyfriend and lead singer of the britpop band Suede, Brett Anderson. Anderson was not only Frischmann’s ex boyfriend, but also one of Albarn and Blur’s primary musical competitors, and as a result other members of the band have reflected that in retrospect, the split between Albarn and Frischmann was an accident just waiting to happen even if they couldn’t see it at the time. Albarn’s drug problem certainly did not help the situation. And so after late 1997, the couple split in what Albarn himself described as “a spectacularly sad end.”

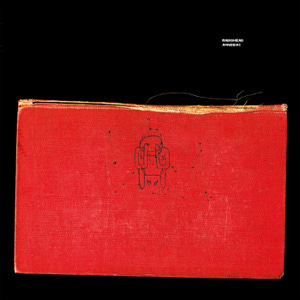

Another factor that impacted the creation of 13 was the band’s unanimous decision to have electronic music artist William Orbit produce the album, instead of their longtime producer during the britpop years, Stephen Street. This helped push the band into a more electronic and experimental direction with their sound on the album, but tensions were high throughout the recording (another similarity to Radiohead’s production of Kid A). As drummer Dave Rowntree put it, band members would frequently not show up to recording sessions, or would show up drunk and end up becoming abusive and storming out. As Orbit put it, Graham Coxon and Damon Albarn were competing to have more influence over the record; the former wanting to go in an experimental direction and the latter in a punk direction. Orbit said Coxon eventually won out, but both kinds of sound are present on the album. Coxon himself said for his part that he was “really out there” which made for some great noisy music but did not help ease tensions with the band. Coxon also painted the album’s cover.

Between the rampant drug use, turbulent relations between band members, and the “spectacularly sad ending” to Damon Albarn’s relationship, it is not hard to see why 13 is a very moody album. The three singles all deal with these subjects directly. “Tender” is an almost 8 minute long, gospel choir fueled breakup lamentation. “Coffee & TV” was written and sang by Graham Coxon about his alcoholism; the song describes how Coxon would use coffee and TV to unwind while he was in the process of giving up drinking. “No Distance Left to Run” was the third single and is an absolutely heartbreaking song that is practically directly aimed at Frischmann. The song, however, features some of Damon Albarn’s best lyrics. The lines “I won’t kill myself trying to stay in your life” and “I hope you’re with someone who makes you feel safe in your sleeping tonight” in the first verse genuinely give me chills every time. But it wasn’t just the singles. “Bugman” is directly about doing drugs in the city and avoiding shady dealers. “Swamp Song,” “Mellow Song,” “Battle,” and “Caramel” are also more or less directly about drug addiction. Every song on this album is thematically seeped in melancholy, frustration, and struggle.

In terms of the album’s sound, it is even more dense and experimental than Blur. Some songs, like “Bugman” or “Coffee & TV” or “1992” do sound a bit more reminiscent of the band’s traditional sound, with “Bugman” having an especially industrial or punk influence. “Tender” features a fantasic mix of acoustic guitar, big stomp and clap sounding drum beats, and a gospel choir during the chorus. “Trimm Trabb” is a quiet slow burner that eventually explodes into crushing guitar and screaming in the background that at times almost overwhelms Albarn’s vocals. “No Distance Left to Run” has a sound that is painfully sparse, with much of the song being just Albarn’s vocals and ragged electric guitar, to match the incredibly painful content of the lyrics. Both lyrically and instrumentally, this song is the embodiment of heartbreak. Closing track “Optigan 1” is a simple instrumental track crafted with an Optigan optical organ.

13 is brooding, dense, abstract, and at times difficult. It is not an album that clicks after one listen, in the way that Blur was for me. And yet it stands as perhaps the band’s magnum opus. Commercially the album was a huge hit and was met with almost entirely favorable reviews upon release. It was certified gold in various countries and even went platinum in the UK and New Zealand. It was nominated for multiple awards, and although it lost out to other albums such as The Soft Bulletin by The Flaming Lips, the album certainly made its mark. “Coffee & TV” saw heavy radio play, especially in the US, and cemented the band’s reputation here. To me, 13 does not quite top Blur, but certainly is their second best album. Sometimes it takes a while for the full weight and genius of an album to hit me and I think I’m in that phase with 13 (the same thing happened to me with Kid A; it took several months and relistens for the genius of the work to fully hit me). Regardless, it is an essential listen for anyone interested in alternative rock and it is among the best of Blur’s catalogue as a band.

13 came out in 1999. Meanwhile, Radiohead were working on their own brooding, dense, and at times difficult magnum opus, which was also crafted through struggle. The results of this would come to be “the greatest left turn in music history” and one of the best albums ever created, Kid A. I am also going to discuss Amnesiac in my analysis of Kid A before comparing these Radiohead projects to Blur, but we are going to take a look at Kid A first.

The story of Kid A starts in the years following OK Computer. With the extensive commercial success and the even more extensive tour that followed, the members of the band were heavily suffering from burnout, Thom Yorke especially. Yorke became physically ill and described himself in the wake of OK Computer as “a complete fucking mess” and “completely unhinged” and completely disillusioned with rock music. To him, the genre simply just had nothing left to offer. He suffered from writer’s block and could not finish any songs he wrote on guitar. As a result, Yorke began to turn to electronic music as an influence. He wanted to focus on the voice no longer having a leading role, and began to focus more on the sound and texture of the music itself. Thom Yorke led and the rest of the group followed his vision as they were all experiencing similar burnout and fatigue; and although Ed O’Brien had hoped for another rock album, the band unanimously decided that that just wasn’t going to happen.

That being said, the decision to turn in a more experimental and electronic decision wasn’t entirely unanimous at all times. Producer Nigel Godrich noted that Thom was often bad at communicating the ideas that he had, and he frequently did not understand why the other members of the band had reservations. Jonny Greenwood was initially skeptical of the new direction, and was afraid that it would end up as “awful art rock nonsense just for it’s own sake” (although he eventually would become one of the most experimental members of the band and threw himself fully into playing obscure electronic instruments like the ondes Martenot). Bassist Colin Greenwood also was hesitant about the new direction, finding it to be too “cold.” There was a very real feeling that the band might break up during these recording sessions. Thom, still experiencing writers block, was writing songs by taking bits and pieces from incomplete songs he had attempted writing, putting them in a hat, and drawing them to be stitched together at random (which we’ll touch on more later). The band was experimenting with electronic instruments, not the usual rock instruments; modular synthesisers, the ondes martenot (similar to a theremin), and software like Pro Tools and Cubase became the norm. The others in the band beside Thom and Jonny were unsure of how to contribute.

Despite these challenges, the band persevered. The members of the band who were unsure how to contribute found ways to make their craft fit in with Thom’s vision; Ed, for example, began using sustain units on his guitar combined with looping and delay effects. It took many long and grueling sessions. The band had no deadline and recorded in multiple locations. But as time went on, eventually the band fell into a groove of making their own bits and additions individually, then coming back together as a band and putting the parts into a cohesive whole. By April of 2000 the band announced they had completed 20+ tracks, to be split into multiple albums. With minimal promotion, no singles, no interviews, no photoshoots, and the band touring Europe in a custom built tent with no corporate logos, Kid A eventually released in October of that year (although much of the album was leaked and bootlegged before, as the band had been using the Internet to do most of their promotion; one of the first major acts to do so).

Upon release, Kid A was immediately successful. It debuted at number one on UK charts and became the band’s first number one album on the US Billboard 200. The album was certified platinum in several countries. The new sound, however, divided listeners. And it is easy to see why. It is nothing like anything the band had ever done before.

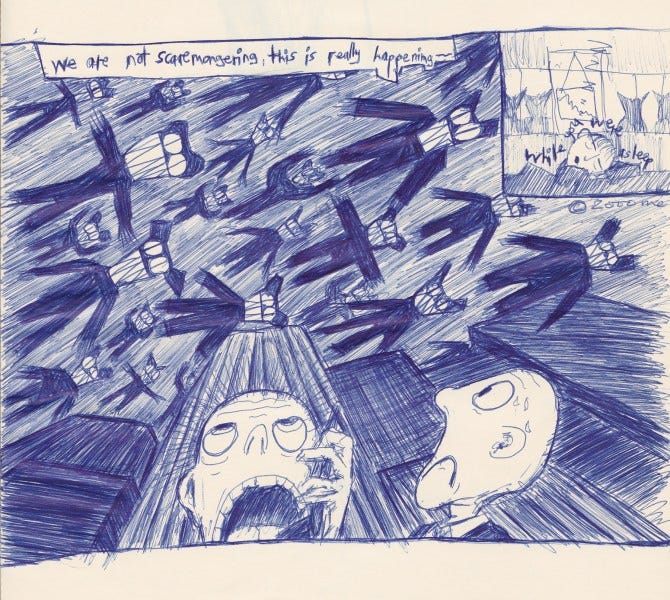

The opening track, “Everything in Its Right Place,” immediately drops the listener into an unfamiliar, yet somehow comforting, soundscape of blanketing synths and completely nonsensical lyrics about sucking on lemons. Remember how I mentioned Thom was writing songs by picking phrases out of hats? It immediately shows. And it doesn’t get any less unfamiliar as the album goes on. “Kid A” is quiet and mellow with vocoded lyrics and some sort of synths that sound like a baby monitor to make for a very eerie effect. The drums and bass for “The National Anthem” were recorded in 1997 and intended to be used for a B-side of OK Computer; the bassline is what keeps the track grounded as it slowly descends into utter insanity with a full brass section. “How to Disappear Completely” has a full string section which was recorded in a 12th century church near the studio and was composed by Jonny Greenwood himself. “Treefingers” is an ambient instrumental made up of digitally processed guitar loops courtesy of Ed O’Brien. “Optimistic” is one of the more conventional “rock” sounding tracks with Thom’s fragmented lyrics; “In Limbo” is an incredibly densely layered arrangement of guitar and electronics with Thom listing coordinates for weather forecasting. “Idioteque” is the crown jewel of the album, in my opinion; a nervous, fast paced, electronic dance song with synth modules, drum machines, and a sample from an obscure French electronic album from the 70s to add to the effect. On top of that, the song is a lyrically compelling story of denial in the face of climate change. It transitions beautifully into “Morning Bell” which carries the same nervous energy and is driven by pounding drum machines. The album closes with “Motion Picture Soundtrack,” a tear jerking song written well before the album, with Thom playing pedal organ on top of harp samples and double bass.

This brings us to Amnesiac. Many have called Amnesiac the companion or sister album to Kid A, because the songs were recorded in the same sessions and in the same sort of process of “each member splitting off to do their own thing then coming back together to form a cohesive whole.” In some ways, this is true. They are similar albums. But they are also very different. Where Kid A was influenced primarily by electronic, ambient, and even progressive music, Amnesiac has a much more distinctly classical, jazz, and even krautrock inspired sound. The closing track “Life in a Glasshouse” was recorded with a full jazz band. Amnesiac was also promoted much more than Kid A, with the singles “Pyramid Song” and “Knives Out” and accompanying music videos. The song “Knives Out” took over a year to complete due to the complexity of the guitar part, which was influenced by the style of Johnny Marr of The Smiths. “Dollars and Cents” had to be trimmed from an eleven minute long krautrock jam into the tense track that it ended up. Amnesiac met much of the same critical success upon release, although today it is one of the more divisive Radiohead albums, as some people find it too similar to or derivative of Kid A. Personally, I think it is firmly capable of standing on its own two feet as an album and is an essential part of the Radiohead catalogue.

So, this brings me to the question- what do the three of these albums have in common? For one thing, they were all born out of tense recording sessions that nearly broke up both bands. In the case of Blur, it actually did somewhat break up the band; Graham Coxon left the band after the release of 13 and would not return until The Magic Whip years later. Not only were the recording sessions tense, but they themselves were born out of deeply troubled moments for the leads of both bands. Thom Yorke felt that he was at the limit of what he could produce musically. Damon Albarn was struggling with drug addiction and a very publicized end to his years long relationship. The mood of the leads of these bands is reflective in all three of the albums. 13 sounds like loneliness and drug addiction. Kid A and Amnesiac, but ESPECIALLY Kid A, sound like loneliness and paranoia. Kid A is one of the few albums that sounds genuinely, truly apocalyptic. The lyrics are fragmented bits of anxiety about political corruption, climate change, and encroaching technology. Moreover, all three of these albums are difficult listens. They are not meant to click on first listen. They are difficult and that is by design. These albums were trying to push the boundaries of what the genre of alternative rock, and really alternative music in general, could be. In the case of Kid A this meant departing from rock entirely. For Kid A it took me walking away from the album and relistening months later for the genius to truly hit me (and lately I’ve been starting to think it might take the throne from In Rainbows to be objectively the best Radiohead album). To be sure, the albums have their differences. Even with the variety of influences and experimentation, 13 is still pretty distinctly a rock album at the roots; Kid A and Amnesiac are distinctly the opposite. But the similarities in their origins, their legacies, and where they would bring each band going forward into the 2000s are just too great to ignore, in my opinion. By 2001, Blur was very firmly the Radiohead of britpop… if britpop even still existed anymore by that point.

Before I wrap things up I do just want to briefly say, I am aware that I wrote quite abit more about Radiohead than Blur in this part. I think this is for a few reasons. For one thing, I was addressing two Radiohead albums in this analysis, not one. In addition, for lack of better wording, the lore of Kid A and Amnesiac is simply just a lot deeper than 13. They took longer to record, they pushed the boundaries further, and overall were just far bigger projects than 13. Also, I just have much more background and experience with the Radiohead albums, as I have been listening to them both devotedly for years, whereas I only discovered and listened to 13 for the first time this year, in 2024. I am not intending to give Blur less attention for lack of interest; I think 13 is a phenomenal album, and one of the best out there. I just ultimately have less experience with it and therefore have a bit less to say. But it isn’t out of a place of being less interested in Blur or that 13 is an inferior album to Kid A or Amnesiac.

Next up I will be posting a small addition to this one; for my birthday, my wonderful girlfriend

got me a vintage edition of Q Magazine from October of 2000, when Kid A came out, with Radiohead at the centerpiece. I didn’t mention it in this post because I was already so far along writing this when I got that gift, but it is worth taking a look at. After that, we will conclude (hopefully) by taking a look at the discographies of Radiohead and Blur in the 2000s, and see how the momentum shifted from Blur being the more prolific band to Radiohead. Hopefully by the end, when we have a holistic look at the careers and discographies of both bands, we will be able to fully answer the question I set out to answer. I hope thus far I have clearly illustrated with evidence that there are many more similarities between these two bands than people perhaps realize. Thanks for reading, and stay tuned.

its cool to see how different artist have different ways of overcoming their hold backs and how they’re able to come back is cool and inspiring as their fans can learn from this and not give up in their own challenges that theyre facing \

I never really think how the artist have their own issues out side of what we can see. But this was a good reminder and a nice way to humanize the artist so we can enjoy them and feel more connected to them.